A New Class of Voting Rights Activists Picks Up the Mantle in Mississippi

Audra D. S. BurchNew York Times — September 25, 2018

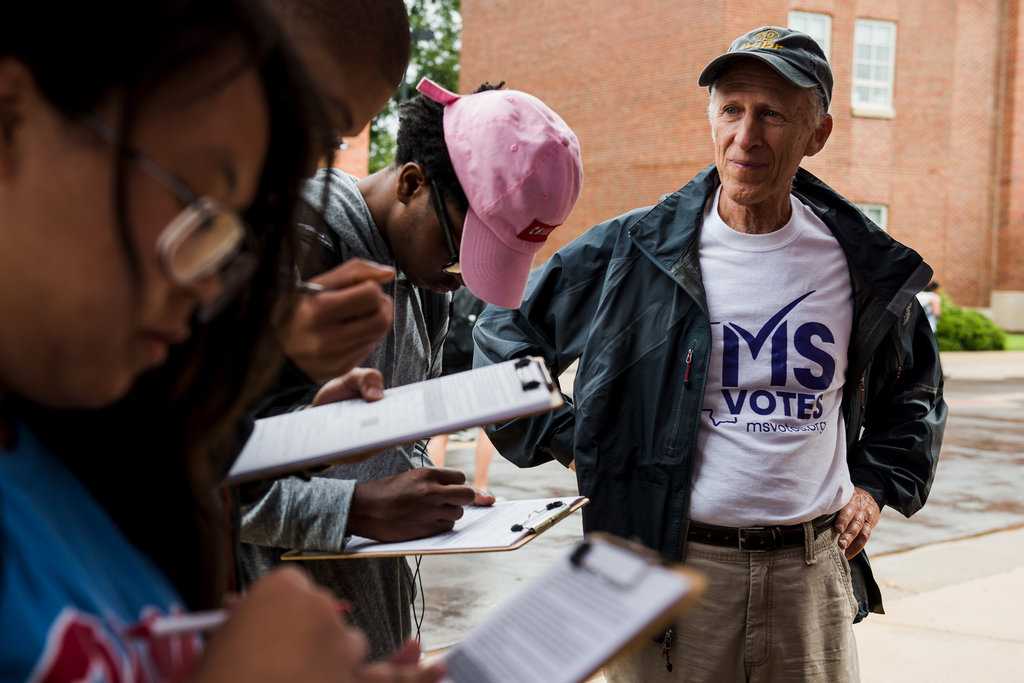

OXFORD, Miss. — The first time Howard Kirschenbaum registered voters in Mississippi was during the summer of 1964, when he was arrested and thrown in jail. The second time was on Tuesday, after returning to the Southern state more than a half-century later to support a new generation of voting rights activists.

In the quiet of a rainy morning, Mr. Kirschenbaum helped to register students on the campus of the University of Mississippi, and before long, he was in tears. Memories of Freedom Summer 1964, the historic campaign to register African-American voters in Mississippi, came rushing back.

“In that moment, there must have been five or six students, all waiting patiently to fill out the registration form,” said Mr. Kirschenbaum, 73, recalling the summer he spent in Moss Point, Miss., 54 years ago. “I am witnessing this moment. They want to vote. They are able to vote. The connection between then and now was so palpable. This is what we worked for all those years ago.”

Four veteran volunteers of Freedom Summer, now in their 70s and mostly retired, returned to the state this week to join a nonpartisan youth group, Mississippi Votes, for a voter registration campaign called Up2Us. Young and old, two full generations apart, gathered at a Jackson church, in nearby neighborhoods, on the balcony of an Oxford bookstore to talk about the perils and stakes of voter activism, then and now.

More than 50 years after Freedom Summer, with voting rights across the nation being whittled away by stricter requirements — requirements challenged in two Mississippi lawsuits as discriminatory — a new generation of youth are taking up the cause to increase voter registration and civic engagement, especially among young citizens and marginalized communities.

“There is a power that transcends our ages,” said Arekia Bennett, 25, executive director of Mississippi Votes, which has 250 volunteers and chapters on nine different college campuses across the state. “We want to dive deep into the veteran stories and learn the lessons of that summer so we can shift the narrative, make our own changes in Mississippi.”

With midterm elections less than two months away and two Senate seats up for grabs, Mississippi Votes is canvassing the state, as the volunteers before them did, hoping to chip away at the hundreds of thousands of unregistered voters. In total, there are about 1,839,449 registered voters in Mississippi, according to the secretary of state. Since August, Mississippi Votes has registered about 2,000.

“This is about creating a culture of civic engagement, not just during the election season. We want people to understand the political landscape and be involved on and off the clock,” said Ms. Bennett, a Jackson State University graduate who wanted to be a physics teacher before turning to civic activism. “We want to engage and empower people so that they see themselves not just as a number but as a viable character in their own lives. This is about self-determination.”

Similar Challenges, but Changing Methods

In 1964, more than 700 college students — mostly white, mostly from the North — brought national attention and public fury to a state that audaciously, violently resisted change. They spent 10 weeks that summer registering voters. Their actions helped shape the framework of the civil rights movement and led, in part, to the 1965 Voting Rights Act.

In Mississippi cities and towns, they worked with local black activists, already steeped in the fight, to dismantle the laws and practices that made it almost impossible for African-Americans to vote. Barriers came in the form of poll taxes and literacy tests, along with the looming threat of persecution and violence. Led by the Council of Federated Organizations, a coalition of civil rights groups, the registration drive was as much about social equality and racism as it was about the power of each vote, the most fundamental tool in the democratic process.

The Voting Rights Act prohibited racial discrimination at the ballot box. But in 2013, the Supreme Court sharply reduced a key provision that required select states with a history of discrimination to seek federal approval before making changes in voting rules that could affect minorities.

Some states have also enacted rigorous guidelines that voting-rights advocates say amount to voter suppression. Some polling places have been eliminated, early voting opportunities have been cut back and voters in some states are now required to present photo identification. Before 2006, no state required a photo ID to vote.

In Mississippi, two recent lawsuits filed by the Southern Poverty Law Center and the Mississippi Center for Justice target the state’s collection of so-called disenfranchising crimes. Offenses ranging from nonviolent charges, such as bribery and forgery, to carjacking and murder are used to disqualify voters. Critics argue that this system, said to be rooted in an 1890 law designed to curb black voters, disproportionately affects African-Americans.

A Mississippi Today study showed that about 56,000 Mississippians were banned from voting because of felony charges over a 23-year period starting in 1994. African-Americans represent 36 percent of Mississippi’s total voting-age population, but make up about 61 percent of those who are ineligible to vote.

“The methods have become more sophisticated, but the broader issues are still in play,” said Jim Kates, one of the Freedom veterans who, along with others, returned to Mississippi to assist Ms. Bennett and the other young organizers.

A Lesson of Fear and Hope

Part of what made Freedom Summer, first called the Mississippi Summer Project, so successful was that it exposed the horrors blacks faced trying to assert basic citizenship. Those experiences were exported to the masses in stark news dispatches. The volunteers, recruited by the Student Non-Violent Coordinating Committee and Congress of Racial Equality activists, trained at an Ohio college, then traveled some 800 miles south by bus or car.

At great personal risk, hundreds of black families hosted the volunteers in their homes. In turn, the volunteers met at black churches, to distribute registration information, helped to fill out forms and escorted them to the courthouses.

The veterans remembered a summer wrapped in fear but also hope. The volunteers were harassed by both the police and white residents. They were arrested and jailed. Beaten. Firebombed. And they were murdered. In the first week of the project, three activists — Andrew Goodman, Michael Schwerner and James Chaney — were abducted and shot just outside Philadelphia, Miss. Their corpses, brutalized and buried, were discovered two months later.

“You never really felt safe. And you never knew if some kind of harassment was going to turn into something more,” said Benjamin Graham, 73, who left the University of California, Berkeley, to spend that summer in Mississippi.

Mr. Graham, who later became a doctor specializing in internal medicine, still remembers with chilling clarity lying in bed one summer night in the house of a Batesville family. It was his first night back in Mississippi after a quick return trip to California. Suddenly, around 2 a.m. his chest began to tighten. His breath had shortened and he was wheezing.

“I started feeling really bad and I honestly believed I had been poisoned by the KKK,” said Mr. Graham, then 19. “It turns out I had asthma, but that just gives you a sense of the kind of stress we were under.”

Building Trust in Different Communities

On Saturday, after an afternoon of training at a church, then canvassing in Jackson neighborhoods, the group — veterans and students from Jackson State University and Tougaloo College — locked arms, forming an intergenerational circle. Then they sang “We Shall Overcome.”

The veterans later drove about 160 miles north to Oxford. They met with more Mississippi Vote student volunteers, from the University of Mississippi, and dined at a soul food diner on the town square. There they chatted about the joy of Southern cuisine and the dearth of rural hospitals and identity politics, but always, always returned to the summer of 1964.

John Strand talked about knocking on doors and trying to convince African-Americans to come to local churches for evening meetings where they could learn more about voter registration. Mr. Graham shared what he believed was one of their biggest responsibilities: bringing a certain understanding and sensitivity into the homes of black voters.

“We were asking people to do something big. There were huge risks for blacks to register to vote at the time. One way they were intimidated was by the practice of putting their names in the local newspaper if they registered to vote,” he said. “That could cost them their jobs. Or more.”

Mr. Graham paused and his words seemed to hang in the air. John Chappell, 21, one of the student Mississippi Vote organizers, turned to Graham and asked: How did you get people to trust you?

“You had to be willing to listen. I think they trusted us, but they didn’t trust that things were going to be okay. And we didn’t say they would,” Graham said. “We knew the risks and we had to be honest about that.”